I spent my first two blog posts developing the historical contexts of both a Clementine Vulgate Bible and an English Polyglot Bible, and now in this final post, I want to discuss the “human element” that composes an integral part of these Bibles as books.

Before I begin, I want to preface my findings regarding the English Polyglot Bible by answering the two questions I posed about stereotyping in my previous post. Stereotyping is a process of printing in which plates are cast of an entire page of text. Having these cast plates eliminates the need to recast the type, and John Wright mentions in his book Early Bibles of America: Being a Descriptive Account of Bibles… that the plates of the English Polyglot Bible were traded between printers, which is how Armstrong and Plaskitt acquired the plates.

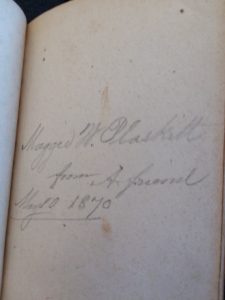

After another trip to the university archives and a second examination of the English Polyglot Bible, I made an important discovery. On the back cover of the pocket-sized tome was a note, addressed to ‘Maggie W. Plaskitt from a friend May 10, 1870.’ This surname matches that of one of the printers of this Bible (Armstrong and Plaskitt).

However, there is also a connection between this bible as well as the “Bible with Engravings” which my classmate Nicole is currently studying. The “Bible with Engravings” was part of the Plaskitt family’s library. In looking at the lineage of this family that Nicole researched and shared in one of her posts, I believe that the Maggie W. Plaskitt to whom the English Polyglot Bible was gifted is Margaret Worthington Plaskitt, the scion of John Plaskitt (the printer) and his wife Catharine Ann Amoss.

The family history lists Margaret Worthington Plaskitt’s date of birth as 1844, placing her at about twenty-six years of age when she received this bible. Although its title page indicates that this Bible was meant primarily for instruction and lessons, taking a step back and approaching it from a different perspective yields an interesting view. The Bible’s pristine condition indicates that it did not see heavy use, and the inscription relates its intention as a gift to Maggie.

Thinking of this Bible instead as a gift rather than sacred text, especially since it was most likely printed by Maggie’s father, gives this book layers of personal and sentimental significance. Perhaps its primary purpose was that of memento, rather than teaching tool.

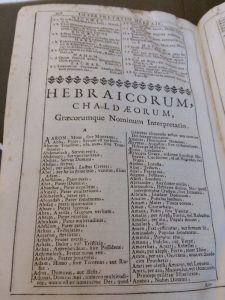

I would be remiss in my duties as blogger of Bibles if I didn’t take a second look at the Clementine Vulgate during my visit to the university archives. Upon closer examination of this Bible, I noticed that it included the supplementary text “The Interpretation of Hebrew Names.” At first glance the inclusion of this textual resource, which was a standard addition to Latin Bibles beginning in the thirteenth century, appears fairly innocuous.

However, placing this Bible in its historical context as a rebuttal from the papacy to the Protestant Reformation makes the inclusion of this text more polemical. As some historical background, the format of the Bible accepted by the papacy was established by the Paris Bible, created in the thirteenth century. De Hamel notes in the course text that theologians at the university in Paris finalized the order of the biblical books as well as the supplemental texts that accompany the biblical text. By aligning with this format and including resources such as the Interpretation of Hebrew Names, the Clementine Vulgate asserts the legitimacy and authority of the Roman Catholic Church.

However, placing this Bible in its historical context as a rebuttal from the papacy to the Protestant Reformation makes the inclusion of this text more polemical. As some historical background, the format of the Bible accepted by the papacy was established by the Paris Bible, created in the thirteenth century. De Hamel notes in the course text that theologians at the university in Paris finalized the order of the biblical books as well as the supplemental texts that accompany the biblical text. By aligning with this format and including resources such as the Interpretation of Hebrew Names, the Clementine Vulgate asserts the legitimacy and authority of the Roman Catholic Church.

Although Pope Benedict XIV (the bishop of Rome at the time this Vulgate was printed) allowed for the printing of Bibles in approved vernacular translations, he did not prohibit the printing of Bibles in the traditional Latin. In doing so, Pope Benedict XIV assumed a middle ground since he did not resist the translation of the Bible into vernacular languages, yet he did not abandon the Vulgate altogether.

From this perspective then, the Clementine Vulgate signifies the papacy’s assertion of their authority and legitimacy as a response to the difficult questions that the Protestant Reformation posed. In its larger historical context however, it marks the beginning of a shift in the Bible instituted by Pope Benedict XIV and his realization that vernacular translations promoted accessibility to the laity.