Title: Polyglot Bible

Date: 1832

Location: Baltimore, Maryland

Publisher: Armstrong & Plaskitt; Stereotyped by L. Johnson

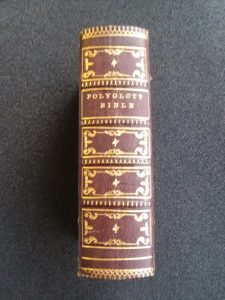

Size: 5 x 3 x ½ inches

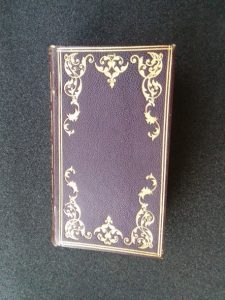

Front Cover

Spine

Bibles serve a myriad of functions, ranging from religious devotional tool to household decoration. As an English translation of the Bible, this text serves as just one facet of a larger project undertaken by the publishers Armstrong and Plaskitt to publish the Bible in ten different languages, not including English. Hence, the term ‘Polyglot,’ meaning “many tongues,” in this Bible’s title. Armstrong and Plaskitt’s vision was highly ambitious, as they wished to publish these translations of the Bible in languages such as Hebrew, Samaritan, and Syriac as well as Latin, Italian, Spanish, and German while keeping to the quarto size, which promoted the portability of this sacred text. According to the preface, it appears that the number of volumes of these bibles would vary to accommodate the languages an individual customer wished to have included in their Bible.

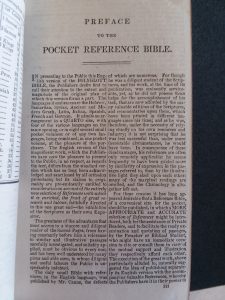

Preface

Old Testament Title Page

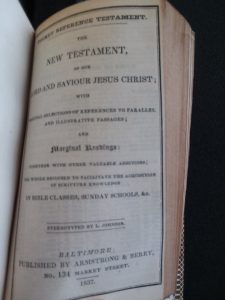

New Testament Title Page

The title page and preface of this Polyglot identify it as a Protestant Bible whose primary purpose was that of teaching tool, specifically intended for use in Sunday schools. The preface expands upon this concept of Bible as reference guide by stating its use “…to facilitate the ready examination and quotation of passages, by the Preacher or Biblical Student, who might have an immediate occasion to cite or consult them in view of the mutual support and illustration they respectively afford each other” (p. iii). This statement aligns with the Protestant philosophy of religion and teaching.

This view of the Bible as a powerful tool meant to be studied and discussed is present in Protestant missionary philosophy. In Christopher De Hamel’s text The Book: A History of the Bible, he notes a crucial difference between how Catholicism and Protestant missionaries attempted to spread their respective faiths. De Hamel explains that Protestant missionaries believed that the mere act of reading the Bible would be sufficient to convert others to Christianity. Thus, the goal of Protestants was to allow everyone access to the Bible in a language they could understand. Unlike Catholicism, the importance of biblical translation did not center on making the text utterly faithful to its original sources, but on translating this sacred text into languages that would make it accessible to people of all countries.

Order of Old Testament Books

The preface of this Polyglot Bible, although it was most likely not a missionary bible meant to convert non-believers to Christianity, echoes this sentiment. It affirms this view that study of the Bible brings with it increased understanding which precipitates greater faith. The purpose of this Polyglot Bible as an instructional resource can be seen in its very structure; on the page listing the books of the Old Testament, two separate lists can be seen. The first provides the actual order of the books as printed in the Bible, but the second list gives the order of the Old Testament books in which they were actually written, accompanied by approximate dates. It is worth noting that the printed order of these books aligns with that of the King James Version of the bible, which was established in the early seventeenth century as the dominant English translation. Like the King James Version, and many other Protestant bibles, the Polyglot Bible omits books such as Judith and I and II Maccabees, which were rejected by church reformers as non-canonical but remain an integral part of Catholic Bibles. This chronology of the creation of the Old Testament books reveals the significance of not only having knowledge of their actual content, but also their context as historical objects. An inscription on the title page of the New Testament, which appears after the entirety of the Old Testament, states its purpose to “facilitate the acquisition of scriptural knowledge.”

Daily Lessons Table

In addition to these lists, a page before the preface contains a chart entitled “Proper Lessons for Public Worship on Sunday Mornings throughout the Year” lists the month and day accompanied by the title and chapter of the books that should be studied at that time. This chart complements the preface’s intention to be used by preachers as well as laypersons. In doing so, it provides a guide for the Protestant minister that is also accessible to the congregation.

While the format and preface of the Polyglot Bible engineer it for use as an educational resource, the physical condition of this book indicates otherwise. For a pocket-sized book meant to portable and often referenced, the appearance of this object does not indicate heavy use. The spine is not split or worn, the pages are intact and some even cling together, as if they have never been turned. An absence of handwritten marginalia demonstrates that this Bible was not used by a preacher or biblical student in a Sunday school or similar environment as originally intended.

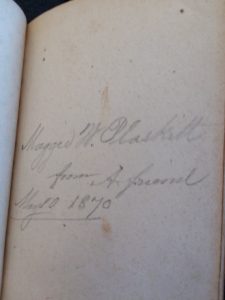

Handwritten Note

The only handwritten text in this Bible appears on the front flyleaf. It is a note to “Maggie W. Plaskitt from A friend May 10 1870.” This inscription reveals that the Polyglot Bible, printed by John Plaskitt, whose was the father of Margaret Worthington Plaskitt, or Maggie W. Plaskitt, was meant to be a gift. Although there is no way of ascertaining the identity of Maggie Plaskitt’s friend, it is likely that this bible held sentimental value for Maggie as it was the work of her father. In this way, there is a fundamental contrast between how John Plaskitt, as publisher, intended this Bible to be utilized and the manner in which the friend intended this bible as a gift with personal value, although these purposes are not mutually exclusive.

The provenance of this Polyglot Bible demonstrates the ability of the Bible, because of its material nature, to assume new roles and meanings depending on the manner in which it is obtained and the context in which it is used or not used. It is this ability that gives the Bible, as a material object that has evolved over centuries, personal significance as well as a connection to a larger, unified faith community.