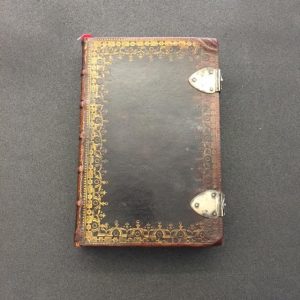

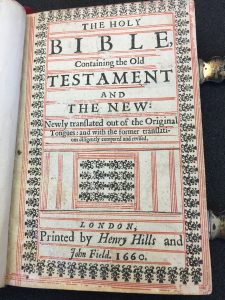

The Holy Bible Containing the Old Testament and the New: Newly translated out of the Original Tongues: and with the former translations diligently compared and revised

London, 1660

Printed by Henry Hills and John Field

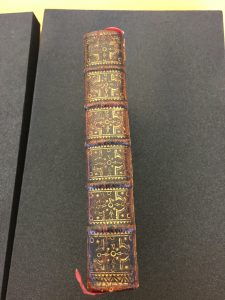

Throughout these entries we have focused on fore-edge paintings, but primarily ones centering around landscapes which was an eighteenth century phenomenon. However, in terms of fore-edge paintings, the final post will concern the first form of fore-edge paintings, those centering around English heraldic designs. These early English fore-edge paintings, are believed to date to the fourteenth century and were exclusively heraldic designs. The first known example of a fore-edge painting that can only be sen when the book is open, dates from the mid seventeenth century, around the time of the printing of the English Bible.1

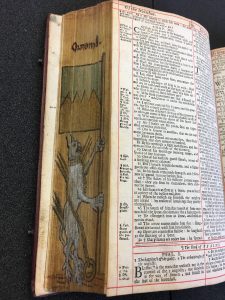

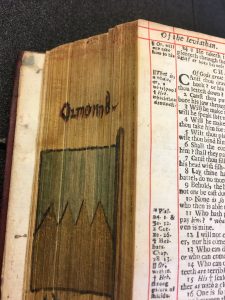

The fore-edge painting in question can be seen when the Bible is opened at the beginning of the Book of Psalms and can be broken into two components. When the book is open at the red silk bookmark, the image on the left depicts a silver griffin wearing a gold collar and chain, with three gold rays emanating from its body holding a standard. This flag appears to have brown or gold mountains under a blue sky. On top of the flag we see the name “Ozmond” which could be the family name Osmond, meaning the flag could be the coat of arms or crest associated with that family.

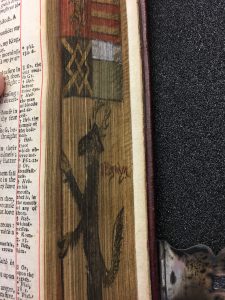

The image on the right depicts a stag or reindeer also holding a standard. The flag itself is broken down into four squares: the top left shows a golden lion on a red background, the top right consists of horizontal gold and red stripes, the bottom left consists of a black background with a gold diamond with an “X” intersecting it, and the bottom right features a green square with a blue horizontal line on top of it. These scenes culminate to create the Standard of Thomas Fitzalen, the twelfth Earl of Arundel, 1381-1415, while each quarter of the standard represents the crest associated with certain individuals: Fitzalen, Flaal, Maltravers, and Clun respectively. On top of this flag we can see the phrase “Therl of Aroundel, Fytzellyn” which again is probably a general family name for the Earls of Arundel and gives further evidence that the standard belongs to the Arundel family. To the right of the stag we can see the word “Bagwyn” which is a mythical creature similar to an antelope but with a goat’s horns and a horse’s tail. In this case this term is probably identifying the stag. (Note that the words from the right side of the fore-edge painting came from the Marion and Henry J. Knott book that catalogued this Bible).

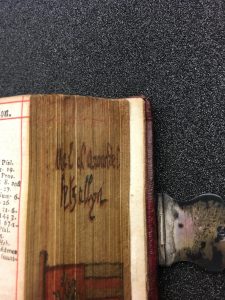

Thus, the fore-edge painting on the English Bible opens up a realm of possibilities in terms of trying to discover both who owned it and why they commissioned this specific heraldic image. The standard indicates that the fore-edge painting is referencing the twelfth Earl of Arundel, someone who lived in the fifteenth century, but the English Bible was printed in the mid seventeenth century, meaning the fore-edge was commissioned not by the Earl but someone else. One may presume that a descendent of Thomas Fitzalen would have chosen this specific image to be painted onto their Bible, however, the small size of the English Bible and the overall quality indicates otherwise. The English Bible does not exhibit qualities that would be present in a Bible purchased by a member of the Fitzalen family, who represented members of the oldest class of earldom and who would later become the Stuart Family or the future rulers of Scotland. This issue is further complicated considering the only two names or owners of the English Bible listed are R. W. Fitzpatrick and William Forfsteen, two individuals who do not seem to have any familial ties to the Earls of Arundel. Therefore, this choice of image seems quite puzzling but its presence is most likely the result of a rising trend in England that centered around heraldry and the desire to link one’s past to a “royal” lineage. Overall, the fore-edge painting for the English Bible creates more questions then it does answers, but it does give us some sort of insight into the desires of the patron who commissioned this fore-edge painting, even if they cannot be named explicitly.