Toward a Digital Understanding of Women's Kiosk Literature

The problem of accessibility

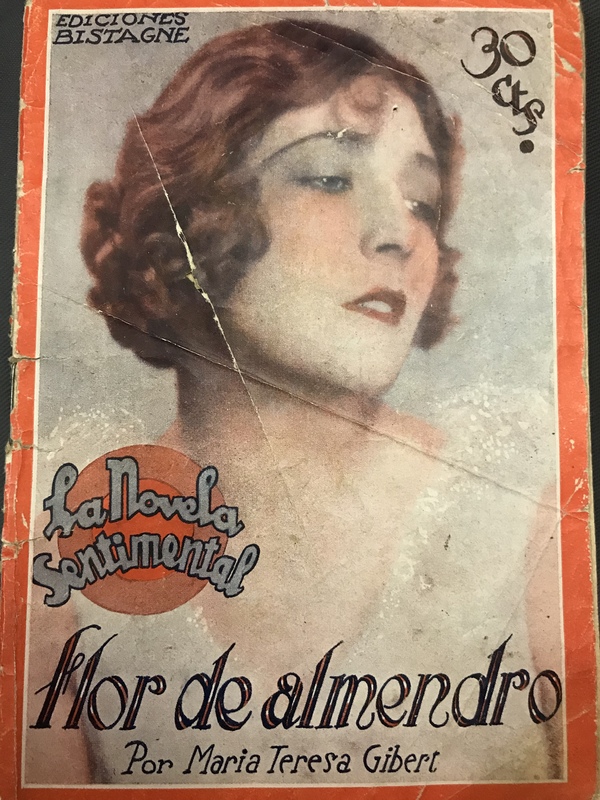

Most of the kiosk literature produced by women remains largely unknown beyond a small circle of specialists. Though important critical anthologies by Concepción Núñez Rey (1989), Ángela Ena Bordonada (1990) and Sonia Thön (2010) have helped bring a small number of authors and works to more mainstream attention, the recovery of kiosk literature is a particularly difficult task. This is due, on the one hand, to the poor condition of extant works. As a commercial product, kiosk literature was highly perishable, quick disposal being its intended fate. The widespread use in Spain in the early twentieth century of cheap, highly acidic paper that over time yellows and crumbles has also ensured that surviving works have severely deteriorated after a century or more of disuse. A further impediment is accessibility. Those works that were not disposed of and that remain intact are scattered throughout national and university libraries, many of whose catalogues or databases remain either incomplete or inconsistent. Many are in the Biblioteca Nacional de España, while others can be found in such disparate locations as the International Institute of Social History (IISH/IISG) in the Netherlands, the University of California Los Angeles, and a smattering of other university libraries.

Kiosk literature and gender

There is an important gendered dimension to all this as well. Women artists throughout history have suffered systematic exclusion from conventional literary histories, but the women writers of Spanish kiosk literature have suffered a double exclusion. The first, based on their sex, they share with a long list of women who are either still forgotten or whose legacies have only been recovered in recent decades. The second exclusion concerns traditional ways of doing literary history throughout the twentieth century. In Spain the privileging of ‘high’ culture over stigmatized ‘low’ culture, particularly under the Franco dictatorship, exacerbated a general disinterest among scholars in popular culture. Mass-produced kiosk literature was hardly thought of as worthy of ‘serious’ attention by critics until the second half of the twentieth century.

Can digitization be a feminist act?

Yes.

Many of the works and legacies of these women remain forgotten. One of the aims of feminist scholarship has always been the recovery of these forgotten legacies and the examination of the social and cultural structures that have led to the exclusion of these women from literary histories. The ongoing, yet incomplete, digitization of their works ultimately recovers, preserves, and makes accessible a scattered corpus of physically deteriorating works.

The digital preservation of female-authored kiosk literature, with its inherent disposability and obsolescence, invites us to consider more broadly questions of women’s involvement in and subsequent disappearance/exclusion from national literary canons.

The women writers of kiosk literature experienced a double marginalization. Indeed, kiosk literature as a popular genre was excluded from Spain’s national canon because of the historically contingent distinctions between “high” and “low” culture. The over fifty women who produced such works were thus excluded by default. But the creation of a national literary canon also rests on a fundamentally gendered division between the “masculine” qualities of “sophisticated” or “high” culture and the supposedly “sentimental” or “feminine” literature of the masses. Women were therefore excluded because gender is a principal informer of what is included and what gets left out of literary histories. In fact, the female-authored short novels of the time not only raise important questions about the role of women in a rapidly modernizing Spanish society, but also evince a modern self-awareness of these gendered conventions, of having been preceded by a tradition of “feminine” popular literature.

Thus, digitization serves an inherently feminist purpose. It is necessary to our continued understanding of the ways in which women writers of the early twentieth century carved out their own space in the literary scene of the time. More importantly, the digitization of this corpus—a corpus which in many ways provides special insight into the contributions of women writers in the development of modern Spanish literature—forces scholars to correct the gendered and sexist processes by which these women were excluded.