K McGowan

Loyola University Maryland is a Jesuit institution founded under the name of St. Ignatius of Loyola and educates with influence from its Catholic roots. This smaller community within “the city that reads” has its own unique reading habits, as it is a learning community with a religious foundation. When Loyola was first founded in 1852 the faculty was completely comprised of Jesuits, but as time went on the Jesuit community became smaller. Throughout the years the school has also become more modern. These changes can be seen from the acceptance of women to even the novels that were read on campus, however, even with these changes Loyola’s Catholic identity still remains because of the dedicated Jesuit community.

Reading is an important part of being a Jesuit. St. Ignatius himself discovered his faith after being wounded in battle as he was forced to the confinement of his bed and took to reading religious texts (Byron, 2). Some of the Jesuits at Loyola are also professors and therefore study the subject they teach on along with the religious texts they read. As faculty members of a college, the Jesuits have a mission to help young adults grow into well-rounded and active members of society. To do so, Jesuits try to instill certain “habits” in their students and in this list, amongst praying and reflecting, is the habit of reading (Byron, 28).

Although it may seem obvious that reading is important to an education, it is more than just reading textbooks. “The lifelong quest for knowledge and truth is virtually impossible to pursue without reading good books. So a genuine Jesuit education will never, in my opinion, be achieved if reading stops when post collegiate life begins” (Byron, 29). Part of the Jesuit mission is for students to learn to become lifelong readers and, furthermore, readers of quality texts, however, by becoming a Jesuit educated reader, students are confining their reading habits to that of their religious teachers.

Since the Jesuits are Christian men, it is clear that their lifestyle, including their reading habits, would be conservative. The Jesuits of Loyola appear no different and have been this way since the college was first founded. St. Thomas Manor is a Jesuit house in southern Maryland that held a library of texts. In the 1840’s the Jesuits were seen to have read mostly religious manuscripts with readings such as “The Popes Essays” and “Annual of the Church” (Ward). By remaining within the non-fiction genre the early Loyola Jesuits were not novel readers, a trend that continued into further decades.

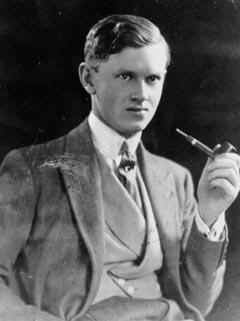

In 1947 Father Xavier Talbot became president of Loyola College bringing many modern changes to the school. Unlike other Loyola Jesuits, Father Talbot was a fan of fiction works. Along with being editor of the Catholic magazine, America, Talbot also founded the Catholic Poetry Society of America as well as the Catholic book club (Varga Waugh, 1). Father Talbot was a novel reader, and enjoyed combining his loves of literature and Catholicism.

In 1947 Father Talbot announced that Loyola would grant an honorary degree to author Evelyn Waugh. Even though Waugh was Catholic, his novels caused controversy amongst religious communities. Father Talbot saw past Waugh’s nontraditional material and instead saw that the author was a brilliant writer with insightful criticisms about society, even if that included the Catholic Church.

Much of this controversy came from Waugh’s novel Brideshead

Revisited, published in 1942 and which depicted a homosexual relationship.

Critics also found “annoyance with Waugh’s portrayal of the faith as it was

lived and understood by the denizens of the fictional Brideshead” (Varga Waugh,

2). To many Loyola Jesuits, this content opposed Catholic values too much and

therefore the author should not receive the degree. In a meeting about this

issue it was argued, “that [Waugh’s] books are shocking, and the conferring

of the Degree would create great opposition.” There was also “no reason why

we should seek to give a degree to a foreigner. Evelyn Waugh means nothing to

Loyola College” (Talbot). This strong opposition is exactly the reason why Father

Talbot argued to give the honorary degree to Waugh, as he believed receiving

a degree from a Jesuit institution would “stop the moral carping” (Varga Loyola,

340).

Father Talbot continued with his original plan and informed Evelyn Waugh that

he would be receiving a degree from Loyola College. Waugh was very thankful

for the honor and wrote to Father Talbot:

“I should be particularly proud since, though I was brought up a Protestant, I can claim a Jesuit education. I was instructed for the Church by a Jesuit and received in a Jesuit Church in London Everything I know worth knowing was taught me by the Society” (Waugh Letter).

Although excited, Waugh was hesitant to accept the degree, as he knew how controversial he had become in the religious community. He was nervous people may question Loyola if they knew it was the kind of institution that awarded writers who went against their morals and faith. In his letter to Father Talbot, Waugh continued by stating:

“I have a story appearing shortly which is bound to shock numbers of good people. It deals with the lives of morticians in a Los Angeles mortuary in a gruesome way. It points no moral...Would a work of this kind become a Doctor of Loyola? I leave the verdict to you” (Waugh Letter).

Talbot had no qualms about his decision, recognizing the novelist for his writing style, critiques on society, and Jesuit background. Loyola granted Evelyn Waugh with an honorary degree in 1948.

The novel Evelyn Waugh had referenced in his letter to Father Talbot was The Loved One, published in 1948 just after Waugh received his Loyola degree. The novel is a critique on American society, analyzing a range of topics as it is about a love triangle between three Los Angeles morticians. The Loved One also seems to reflect the experiences Waugh was going through at the time as themes about religion and conformity can be found amongst its dark humor.

|

|

|

|

Brideshead Revisited (1945) |

The Loved One (1947) |

Evelyn Waugh |

The novel begins with a Sir Francis Hinsley who works as a writer for a Hollywood production studio. Although working there for years he faces difficulties conforming to what kinds of films the studio wants. While discussing his newest film with a coworker Sir Francis is told “And now there’s been a change of policy at the top. We are only making healthy films this year to please the Catholic League of Decency” (8). A hierarchy has been established with writers acting as puppets, producing what powerful American societies want. In this case it is the Catholic Church. This is not far off from Waugh’s own life as he faced mass scrutiny from the Church for his works and he used this novel to illustrate the power the Catholics have over even the most liberating of jobs such as writing. Unable to produce a decent movie script, Sir Francis is fired from his job and kills himself out of depression. This may seem like an extreme reaction to the Church, but it proves Sir Francis could not even conform to their ways in death, as suicide is a sin.

One element of Waugh’s writing that makes it so unique and funny is the lack of emotion within the characters. The three main characters are all morticians and therefore see death as their business. Sir Francis’ nephew, Dennis Barlow, is a mortician for a pet cemetery who found his uncle “strung from the rafters” (37). Although he had never seen a human corps before, Barlow simply found the sight “rude and momentarily unnerving; perhaps it had left a scar somewhere out of sight in his subconscious mind. But his reason accepted the event as part of the established order” (37).

Waugh also takes emotion out of love. Barlow falls for a mortician named Aimée at Whispering Glades, the funeral home and cemetery he visits to arrange his uncle’s funeral. At the same time Aimée is courted by Mr. Joyboy, the head mortician at Whispering Glades. To decide which man she wants to marry, Aimée formally writes letters to an advice columnist, detailing the pros and cons of each man and asking for a final answer as to what she should do. This is completely opposite to many romance novels, where the female protagonist is painfully caught in the middle and must eventually let her heart decide. She originally chooses Barlow, who wooed her through poetry and knowledge of fine literature, placing Waugh’s profession as the heart and emotion of the novel. However, Barlow is exposed as a fraud, and when Aimée is left to choose between both flawed men she kills herself with “no letter of farewell or apology. She was far removed from social custom and human obligations,” therefore leaving the world without any trace of passion (150).

This lack of emotion in death and love also removes any religious aspects the novel might naturally have. Waugh is careful to control each time religion comes to play into the novel and is sure to leave it out in the idea of marriage, which is illustrated as a formal contract, and in death, where Waugh does not entertain the idea of heaven and hell within the text. The dry characters also cause the reader to feel unattached to them. When Aimée is deciding which man she wants to marry there is no urge comfort her and when she commits suicide the reader knows it is not a death out of love and extreme passion, but instead a solution to her indecisiveness. However, by being unattached to the characters, even in death, the reader can understand their role as morticians and their ability to see death without emotion.

The coldness in the novel is also critical to Waugh’s criticism of American culture and, particularly, the church. Aimée, although charmed by Barlow, does not know if she is in love yet and seeks an answer from Guru Brahimin of the daily newspaper. The reader can laugh at Aimée’s inability to understand love and formal approach to marriage however, in the novel Guru Brahimin, “an oracle,” plays the role many priests play (100). Although a more modern world, people “reared their questioning heads in this Eden too, and to all readers the Guru Brahimin offered solace and solution” (100). The reader is also able to see behind the scenes and realizes Guru Brahimin is really an average man who gets fired from his position and, in a drunken rage, tells Aimée to kill herself in order to solve her problems. Aimée, a dedicated follower of the Guru, takes his orders and ends her life. This revelation that Brahimin is really just a stressed out newspaper employee gives insight into the corruption within groups that serve as “spiritual directors” such as the Catholic Church (100).

In the novel love serves as a business for the newspapers, which publish advice on people’s life problems. Death is also seen as an industry as the three morticians pride themselves on their skills of preparing the dead for viewing and their efficiency in laying them to rest. It is then only natural that Evelyn Waugh would introduce religion into his novel as a company. While asking Aimée how she entered their “trade” she explained: “I look Art at College as my second subject one semester. I’d have taken it as first subject only Dad lost his money in religion so I had to learn a trade” (Waugh Loved One, 90). Here religion is like an unreliable stock market where some win and lose. Again, Waugh emphasizes that religion is not something that is completely reliable. It is, instead, a business that works to run the culture of America.

The system of religion is further explained when Barlow decides that he will leave the mortician business to become a non-sectarian pastor who specializes in funerals. When talking to The Reverend Errol Bartholomew, Barlow is described the process of becoming a non-sectarian clergyman.

“Tell me, how does one become a non-sectarian clergyman?”

“One has the Call.”

“Yes, of course, but after the Call, what is the process? I mean is there a non-sectarian bishop who ordains you?

“Certainly not. Anyone who has received the Call has no need for human intervention.”

“You just say one day ‘I am a non-sectarian clergyman’ and set up shop?”

“There is a considerable outlay. You need buildings. But the banks are usually ready to help. Then, of course, what one aims at is a radio congregation” (122).

This process is just like any business venture. Barlow has an ambition to raise his earnings and social class, realizing the church is a morally acceptable and easy way to do so. Also, by being non-sectarian, he does not actually have to understand or believe in religion. He can continue his current lifestyle and spend his life blessing the dead—using only the knowledge he has now. Bartholomew continues to explain that: “The competition is getting hotter every year, especially in Los Angeles. Some of the recent non-sectarians stop at nothing—not even at psychiatry and table-turning” (122).

Everyday people are rapidly entering this business and claiming to be part of the Church, however, they do not actually have the knowledge or morals the Church bases their values off of. Using non-sectarian clergymen as the example of a religious figure within the novel, Waugh is commenting on how fake every aspect of the American lifestyle is. Everything, even religion, is only for show and for advancement in social class. He is also individually criticizing the Church for its corruption and role as one of the controlling American industries.

Dennis Barlow is not the only character with a lack of religion. When burying Sir Francis, Barlow chooses to have a non-sectarian ceremony since he lived as an agnostic. Similarly, Aimée learned from society that morals and religion can be separated and that to have one, you do not need the other. When Aimée describes herself to the Guru she states: “I am progressive and therefore have no religion” (128). This changed occurred at college when Aimée realized it was modern and socially acceptable to no longer have a religious affiliation. However, despite her lack of faith, Aimée is still “ethical” and needs her husband to have these same values (128). The abandonment of religion by almost every character in the novel, including the clergymen, illustrate that religion was only a social standard. Once it became acceptable to leave their faith without leaving a social class, many did so and were still able consider themselves moral. The progression of so many people becoming unaffiliated also beckons back to the idea that religion is changing in America and Waugh’s book should not come under such harsh criticisms by the traditional Catholics who are not seeing the current role religion plays.

Now that religion is no longer needed to be considered moral, people use the Church as an industry to make money, as seen with the unaffiliated clergymen. In Waugh’s novel, business is religion and Aimée even refers to the funeral home as “the religion of Whispering Glades.” Also, the most emotional scene in the novel occurs when Aimée is dead and Mr. Joyboy begins to sob uncontrollably, worried that the death of his assistant may cause his business to crumble (143). The powerful American industry Waugh discusses is also centered around the theme of control. The corrupt Church, as seen in the clergymen and represented in the Guru, wants to control the people’s ideals while each character is only worried about being in control of their life, for when things become unpredictable, they breakdown or kill themselves.

Evelyn Waugh’s use of unconventional topics and dry humor are sure set him up for criticism by many conservatives. It is no surprise then that the Loyola Jesuits, who read mostly non-fiction and religious texts, would dispute giving Waugh an honorary degree from the college. Despite receiving the degree, Waugh took the backlash from the Catholic community, from whom he claimed his education, personally. In his next novel, The Loved One it is clear that he inserted his anger into the text, turning the tables and critiquing religion’s place in American society.

The lack of faith not only produces cold, business-minded characters, but also distanced religion’s role in morality in this new, progressive era. Waugh changed the Church from a secular place of values to another American company, fighting for money and pushing their ideals on the people. However, although being unable to produce what the Church wanted, Waugh wrote for the modern American who appreciated his works. Some of these Americans were found at Loyola and were even amongst the Jesuits, as President Father Talbot initiated the idea of giving Waugh a degree. Despite the many traditional Catholics at Loyola, who continue to read conservative books, the college began to modernize with the country and accepted Waugh’s writing, thus giving him a place in American literature.

Varga, Nicholas. “Evelyn Waugh in Baltimore 1948 and 1949.” Folder: Waugh Collection.

Waugh, Evelyn. The Loved One: An Anglo-American Tragedy. Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1948. Print.

Series: Files. Subscribers: Father Francis Talbot. UP Box BT #14. Folder: Waugh Collection, Loyola University Maryland.