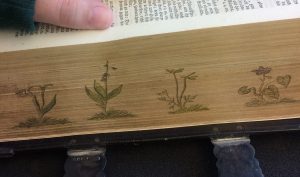

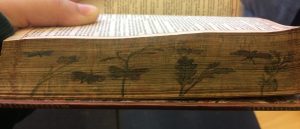

Having uncovered some of the content of my split fore-edge nature studies, I set out to explore their context. Conscious of the unique subject matter of the paintings and hoping to identify an artistic tradition that could encompass their focus on nature as well as their meticulous attention to detail, I stumbled upon botanical art, a discipline which, unbeknownst to me, is a sophisticated and highly precise art prominent in both the scientific and artistic fields. Botanical art is defined by its exacting, scientifically descriptive depiction of plant species, as well as an attention to aesthetic appeal, both of which are evident in the fore-edge paintings of Knott numbers 111 and 138.

Knott_111 Recto Painting

Knott_138 Recto Painting

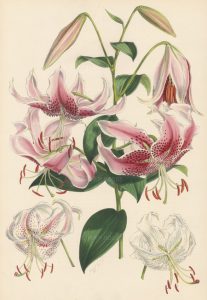

The stylistic conventions of botanical art were highly regimented – in traditional botanical art, the expectation is that a successful drawing or painting will represent a plant such that the genus is recognizable, if not to the species (Ben-Ari). The light source is generally oriented in the top left of the composition, but the effects of light and shadow are minimized so as not to obscure the features of the plant. While this rule does not apply to the miniature paintings on the fore-edges of the Knott books, other traditional aspects of botanical art certainly do. One of the primary stylistic features of traditional botanical art is the rendering of the subject at eye level against a blank background, a rule to which both the paintings on Knott 111 and 138 adhere. Watercolor is also the most commonly used in botanical art, and the fact that it is also the primary medium of fore-edge painted books may offer a possible explanation for the choice to incorporate decorative botanical paintings into these fore-edge paintings (Ben-Ari).

https://www.asba-art.org/sites/default/files/styles/sidebar450/public/article/70%20Lilium%20speciosum%20Fitchresize.jpg?itok=ba1SExjn

While the origins of botanical art are ancient and largely practical, there is a notable spike in the prominence of botanical art as an aesthetic style between the mid-eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries. This trend could, in part, be attributed to an increased interest in scientific discovery and exploration, or to the widespread popularity of flowers that initiated the eighteenth-century boom in horticulture in Europe. The same people investing in botanical art were those wealthy individuals who were carefully cultivating gardens, and many of the artists of this style were women from aristocratic families (Flannery 117). In the latter half of the nineteenth century, however, botanical art declined drastically, likely due to the professionalization of scientific pursuit and the emergence of photography, which was seen as a replacement for naturalistic drawing, particularly in scientific fields (Ben-Ari). This time frame is consistent with the known dates of the books, as well as with the popularization of fore-edge painting, and helps to date the books to sometime within this period.

There are, naturally, some problems with this classification of the Knott split fore-edge books. Most significantly, only number 111 can be definitively classified as a botanical painting – while insects were sometimes incorporated into botanical art, they were rarely the focus as they are on Knott number 138, and Knott number 198 has none of the features of botanical art, favoring fauna over flora as it does. This is, however, a start to explaining these paintings, which will hopefully lead in promising directions.

-Rosie Waniak

Ben-Ari, Elia T. “Better than a Thousand Words: Botanical Artists Blend Science and Aesthetics.” BioScience 49, no. 8 (1999): 602-08. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/bisi.1999.49.8.602.

Flannery, Maura C. “The Visual in Botany.” The American Biology Teacher 57, no. 2 (1995): 117-20. doi:10.2307/4449936.