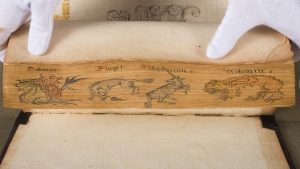

One of the first things that interested me about Francis Bacon’s book, Sylva Sylvarum: or, A Natural History (Knott 165), was the representation of the four medieval beasts in the fore-edge painting. I thought it was strange that someone would put a painting that incorporated elements from medieval fables on a book about natural history and scientific observations and experiments. But, when I started researching the role of medieval beasts and fables in the theology, philosophy, and science, I realized that many scholars used these references to help people understand the world around them.[1] The fore-edge painting on Sylva Sylvarum seems to portray a phoenix, tiger, unicorn, and a crocodile. I found that the phoenix is often a symbol for new life. When the phoenix dies, its ashes are turned to liquid, and the liquid then becomes a worm who will eventually grow and mature to its previous form—the phoenix. Due to its focus on rebirth, the phoenix was also used by Christian theologians to demonstrate and teach the beliefs regarding Christ’s Resurrection.[2] Through this understanding of the phoenix and what I know of Bacon’s book so far, I think this representation of the phoenix on the fore-edge painting could connect with Bacon’s theme of improving human life. For example, he discusses how to preserve and prolong life in some of his experiments—connecting to the long life of the phoenix demonstrated in the story.

Fore-edge painting of four medieval beasts on Francis Bacon’s Sylva Sylvarum: or, A Natural History, 1658, Knott 165.

Fore-edge painting of four medieval beasts on Francis Bacon’s Sylva Sylvarum: or, A Natural History, 1658, Knott 165.

When researching the symbolism of the tiger, I found that the tiger, or tigress, is often associated with qualities of courage and quickness. But, the story of the tiger also highlights its main weakness—distraction. When one of the tigress’ cubs is stolen by thieves, the tigress quickly chases after them. Unfortunately, as soon as one of the thieves drops a mirror on the ground, the tigress is immediately distracted by her own reflection and loses sight of the cub. In keeping with the theme of human progress, this story suggests that human beings need to be aware of possible distractions, but push through them in order to better themselves and the world. The story of the unicorn presents this kind of idea of pushing forward and bettering oneself as well. Like the tiger, the unicorn is known for its quickness. The unicorn is presented as a very powerful animal that is not held back by anyone and is often considered a spiritual symbol for Christ.[3]

Fore-edge painting of pheasant or Bird of Paradise perched on a stump, Orator Marianus, 1740, Knott 57.

Fore-edge painting of pheasant or Bird of Paradise perched on a stump, Orator Marianus, 1740, Knott 57.

The fore-edge painting on the book, Orator Marianus (Knott 57), is of a bird perched on a stump. It is unclear whether the bird is a pheasant, dove, or a representation of the bird of paradise. I found that the dove is often a symbol of peace. It does not cause trouble and is known to provide guidance for others.[4] I also researched the bird of paradise and found many references to Christianity, specifically regarding the belief of eternal life. I need to do more research on this, because I think a better understanding of the bird of paradise and its relationship to theology could possibly reveal a connection to the text. But, in order to understand these paintings and books, I think it is important to recognize the role animals, or medieval beasts, played in people’s understanding of themselves and the world.

Sara McAleer

Bibliography

- Edmund Hussey. The Antioch Review49, no. 4 (1991): 614-15.

Schrader, J. L. “A Medieval Bestiary.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 44, no. 1

(1986): 1-55.

[1] M. Edmund Hussey, The Antioch Review 49, no. 4 (1991): 614-15.

[2] Schrader, J. L, “A Medieval Bestiary,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 44, no. 1 (1986): 1-55.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.