As mentioned in my previous blog post, the Scottish Bible has a double fore-edge painting of views from the German Rhine river, specifically the cities of Cologne and Heidelberg. The image of Cologne Cathedral in the fore-edge painting is particularly interesting because it features the completed cathedral which was not finished until 1880, fifty years after the Scottish Bible was printed in 1830.

As with all fore-edge paintings we cannot assume that the painting is contemporary with the publication or binding date of the book; fore-edge paintings could have been added to the Bible at any point in its life. Similarly, dedications or other names in the book may not be a clear indication either of the ownership of the fore-edge painting. Therefore, this fore-edge painting was clearly added after the Bible was printed and even though there is a stamp dedicating ownership of the book to R. Cumming, especially without a date we do not know if he commissioned the fore-edge painting for this Bible or not. Even though we do not know the exact date of the fore-edge painting its iconography matches typical fore-edge paintings of the 1800s which consisted of more complex scenes than picturesque landscapes made famous by Joshua Gilpin in the latter half of the eighteenth century.1 Instead of just a simple landscape, more complex cities, landscapes, or activities like fishing and hunting would be employed in fore-edge paintings like the one featured in the Scottish Bible.2

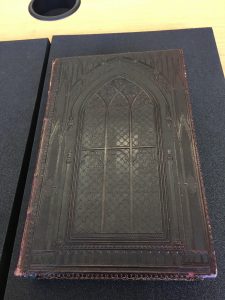

Whether or not the Scottish Bible belonged to R. Cumming during the late nineteenth century when the fore-edge painting was most likely created, the image still connotes notions of tourism and the Grand Tour, which was an educational trip taken by primarily wealthy British men and women throughout Europe in order to expose themselves to classical and Renaissance art and architecture. We may never know if Cumming went on the Grand Tour or something similar to it, but the German fore-edge painting leads one to believe that travel and potentially the desire to sit on the bank of the Rhine river contemplating the medieval associations present in Cologne Cathedral, was on the mind of whomever commissioned the painting. Also, the choice to include Cologne Cathedral in the fore-edge painting and elements of Gothic architecture on the cover of the binding, establish a possible link to the Gothic Revival movement. The Gothic Revival movement emerged in nineteenth-century England with roots in a re-awakening of High Church beliefs and practices throughout Britain. Architecture like Cologne Cathedral, emerged in an attempt to conjure up the religious beliefs and practices of the medieval period, something we see in the inclusion of the Gothic pointed window on the binding of the Scottish Bible. Whether or not the binding and the fore-edge painting were commissioned at the same time and by the same patron, they still give this Scottish Bible a certain quality, almost making it more “holy” because of this direct link to the Gothic period where there was a strong focus on religion. Overall, through an examination of the decorative details of this Bible in comparison with its historical context, we can begin to piece together what was important to the R. Cumming or anyone else that owned this Bible.